Inquiry in Social Studies

I’ve always loved teaching Social Studies through inquiry. Start with questions students have, and then let them explore, research, and learn from there! This approach has led to biographical essays about inspirational historical and contemporary figures, case studies about different countries, companies, and Virginia Indian tribes, investigations into various holidays, and so much more. My hope is that teaching Social Studies through inquiry supports my students in continually learning about the world in a curious and open way.

Some essential parts of inquiry in Social Studies (for me) are:

Keep the final product open or at least open ended! There are so many ways to share what you learned - let students figure out the best way to do so and personalize it.

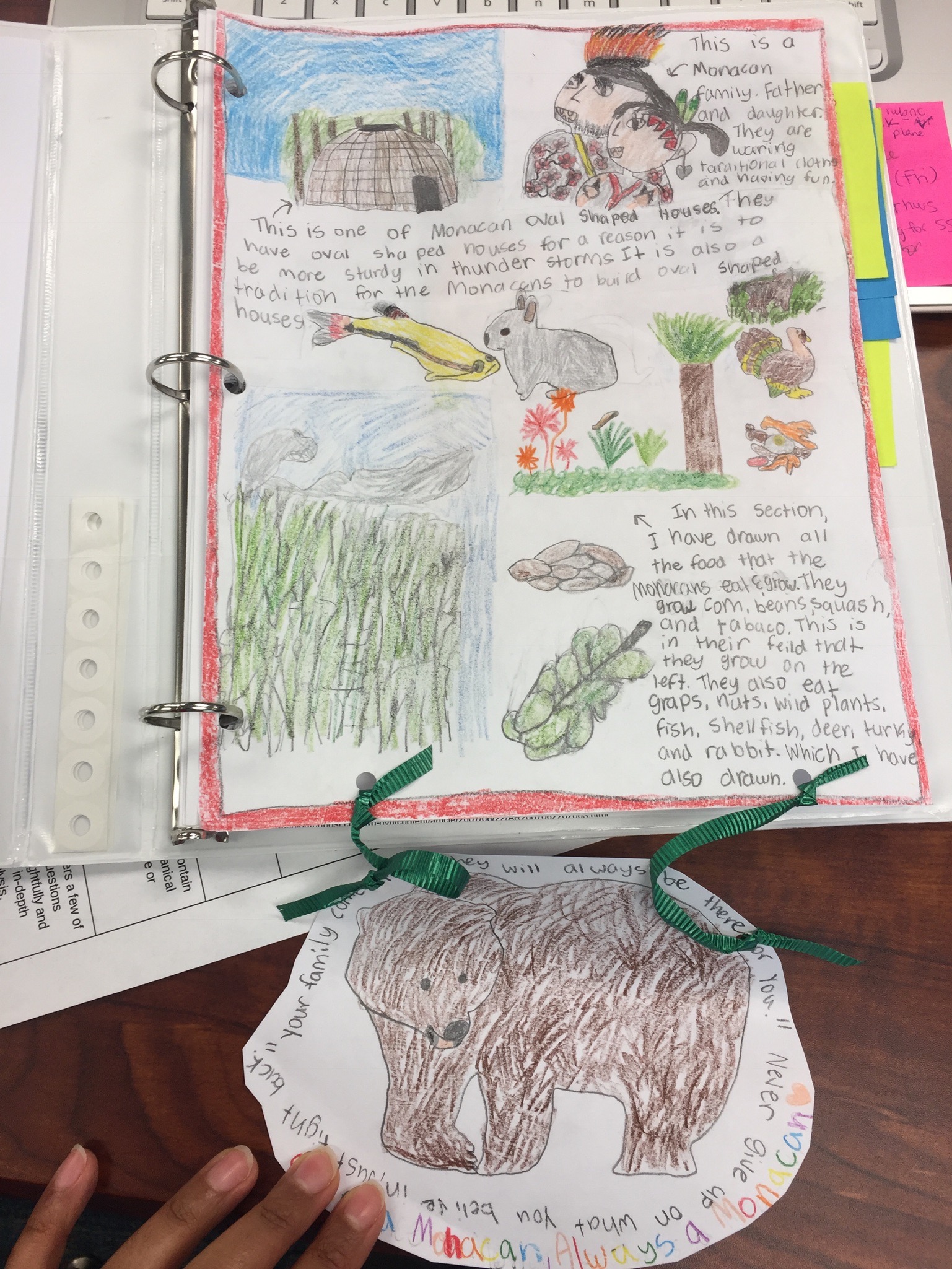

Encourage creativity! We asked our students for annotated illustrations of the Virginia Indian tribe they studied, and every single one of them interpreted that a different way.

Be clear that what you are learning is limited in scope and in perspective. Use a concrete example to show that sweeping statements about all individuals who share an identity (or other) trait don’t work. I often use my wearing glasses as an example of what is generally true, but not always true for people who wear glasses versus what I prefer. The concrete example helps students to see the fallacy of overgeneralized statements and they can suggest how to reframe or rephrase statements to avoid this. Some words and phrases my students brainstormed included: usually, sometimes, some, in this instance, this example, one possibility (and of course, there are more).

Always start with student questions! This is where inquiry begins - with asking a question. Keep in mind that students may need an introduction to a topic or some background knowledge before they can pose meaningful questions. Photographs, video and audio clips, and primary source documents are a great way to get students interested in a topic and give them some context to start asking questions.

Find out what students already know (or think they know) and act accordingly! Background knowledge is so important to learning and understanding. So is identifying and clearing up misconceptions. Skipping ahead to research and learning new information without engaging in this pre-inquiry step can lead to more confusion.

One example of an attempt to do many of these things was our Native American Studies unit with 5th graders. We started by asking students what they already know about Native Americans, and immediately needed to clear up confusion about names and proper terms (many of our students claimed that saying “Indians” was offensive). One way we did this was by taking a field trip to the wonderful National Museum of the American Indian here in DC. At the museum, our students were surprised to learn Native Americans are still very much present today.

Many of our students shared that the Disney movie, Pocahontas, came to mind when we first started learning about American Indians. So we took some time to delve into an investigation of Pocahontas and see how what we discovered connected with what we already learned and had questions about. Students were shocked to see how quickly they generalized from an animated movie with limited historical accuracy to all Native Americans.

Our takeaways from this information our students shared (and were missing) was that we needed to learn more about American Indians today! So we learned some new vocabulary and background information from documentaries, articles, stories, and more. We also learned about the Virginia Indian tribes as a concrete example of American Indians living near us right now.

Our final project for the unit was a case study! We gave students time and resources to learn about a Virginia Indian tribe. We started with questions like: what do you want to know? What are the 10 most important things to know & share about this tribe? How would you depict your understanding? Students wanted to know SO MANY THINGS! The Top 10 List was a really effective structured way to share their knowledge while allowing them to follow their own lines of curiosity. We also included an “annotated illustration” as something to share to allow creativity and freedom to express their learning in an unstructured (non-written) way. As you can see from one of our students’ finished products (cover photo), they had so much to share.

*An important disclaimer we started our case study work with was to remind students that our understanding is limited! We don’t know everything about an entire Virginia Indian tribe and couldn’t share it if we did.

The best way to do inquiry might vary from class to class and subject to subject, so these are just a few general guidelines we try to follow that have worked for us.